Poisons and Antidotes; part 1of 3: What is a Poison?

Reflections

What is there that is not poison? All things are poison and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison.’

-Paracelsus (1493-1541)

‘Rod of Asclepius’; wielded by the Greek god of healing and medicine.

Lurking at the base of all medical therapy like a coiled serpent is the science of poisons. Often referred to by its own practitioners as a ‘borrowed science’, toxicology finds it’s roots with the ‘poisoners’ of times gone by. Generally speaking, the art and science of healing is inseparable from the concepts involved in ‘poisonings’. As befits the subject itself, this history is one fraught with intrigue, fraud, betrayal and, of course deaths. Although this history is difficult to hear about and ponder, it is part of a wider understanding of what toxins or poisons are, and how they work in us individually and collectively. This understanding is pre-requisite to not only mitigating or even negating the effects of poisons through avoidance, detoxification, and/or antidote; but also to the possibility of the transformation of the poisoning relationship to one of healing.

According to Casarett & Doull’s comprehensive textbook, ‘Toxicology; The Basic Science of Poisons’; ‘One could define a poison as any agent capable of producing a deleterious response in a biological system, seriously injuring function or producing death.’ However, the author goes on to clarify that ‘this definition immediately invites contradiction since almost every substance has this potential’! Paraclecus, physician-alchemist of the late Middle Ages, noted that it was ‘the dose’ that determines whether something acts as a poison. Modern toxicologists speak of ‘the dose and the host’. Anthroposophical medical science might say of poisons, ‘the dose and the entire context in which it is used’ determines toxicity (something’s ability to act as a poisoning agent).

This ‘entire context’ includes a history that dates back to pre-recorded antiquity when the earliest humans used poisons for hunting, warfare and assassinations. Written records dating back to an Egyptian papyrus from around 1,500 BC contain descriptions of recognized poisons. Around 400 BC, there were further works recognizing poisons including biblical references in The Book of Job. The writings of Hippocrates (‘Father of Modern Medicine’) included not only additions to the list of known poisons, but also commentary on dosage, bioavailability in therapeutic use and overdosing. Nicander of Colophon, a Greek poet-physician of the second century BC, wrote poems in hexameter about poisons and antidotes. In fact, the topic became so popular during these times that poisonings in Rome reached epidemic proportions and a large conspiracy of women to remove men from whose deaths they might profit was uncovered. Large scale poisoning behaviors spread and continued relatively unchecked until around 82 BC, as humanity approached the Turning Point of Time, when the first known law against poisonings was issued. Cleopatra, ruler of Egypt until 30BC, was well ahead of her time in her cosmopolitan education and attitude. Unlike her predecessors, she spoke the languages of the various peoples she ruled as well as those of neighboring cultures. Well versed in the sciences and the rites of spiritual initiations, as was usual for a ruler of her time, it is said that she used her knowledge of animal poisons by purposefully falling on her asp (which then dealt her a fatal bite) to avoid being forced to do something that was against her conscience.

The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC)

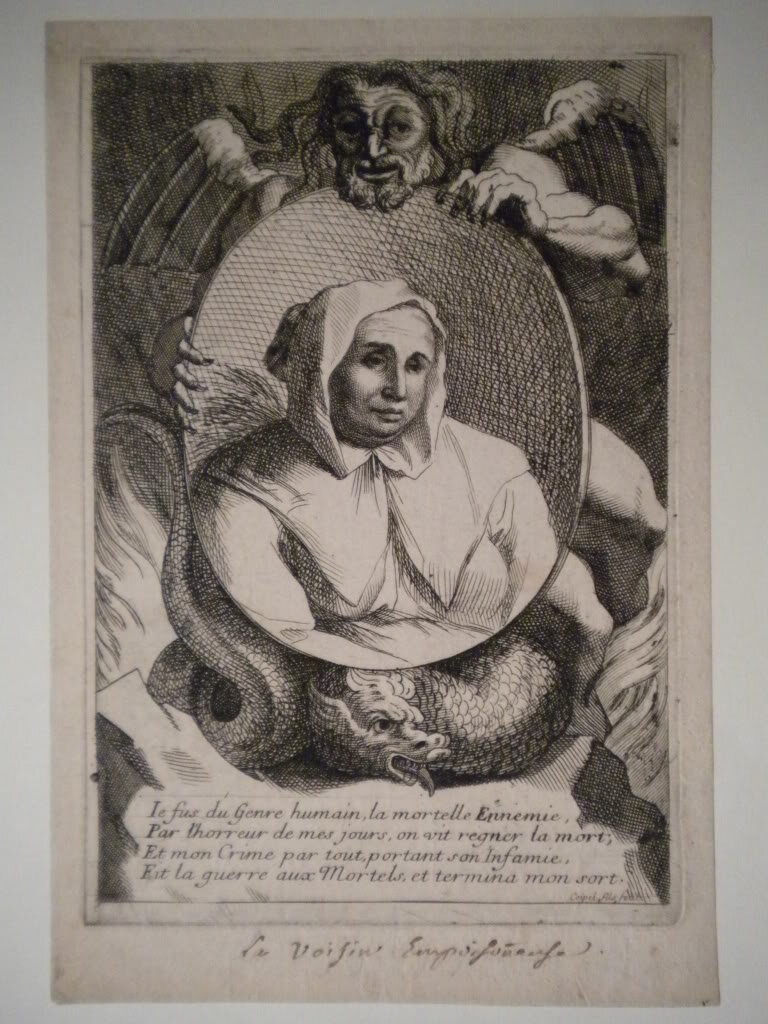

Despite these first indications of an approaching and developing collective conscience regarding the concept of harming someone else to increase ones own well-being, the use of poisoning continued into and through the Middle Ages. However, the character of the efforts began to change in that poisonings became progressively more thought through and methodical; i.e. scientific. During the Renaissance period, prominent families were involved and poisonings were an integral part of the political scene (see Note 1). Women were among the most influential forerunners of this science of poisoning and played a more outwardly visible role both in its practice and its development than was apparent in other sciences. In an age when timeless art was created portraying women with highly developed spirituality who portray the archetypal qualities of wisdom, beauty, and virtue (Madonnas of Raphael, Boticelli, and Da Vinci, for example), it is also a fact that some of the more prominent contributors to the scientific approach to toxicology were women who were involved in the occult black arts. Fortune-teller Hieronyma Spara, a woman who succeeded Toffana (a Italian woman who peddled arsenic-containing cosmetics and creator of the renowned poison mixture ‘Aqua Toffana’), headed an organized club of young wealthy married women who soon became a club of eligible young wealthy widows. The highly intelligent Queen Consort of France, Catherine de Medici, because of her high profile cohort and clientele, had need of developing direct evidence for the most effective poisoning compounds for their specific purposes. Having strong ties to the occult and allegedly to the black arts, she is said to have methodically taken toxic mixtures to the poor under the guise of providing sustenance and then carefully observing and recording their reactions. Her records included how quickly the poisoning took effect (onset of action), effectiveness (potency), the degree of response of parts of the body (specificity and site of action), and the complaints of the victim (signs and symptoms). Her experimentation marked one of the earlier examples of methodical scientific style research in the field of toxicology. Most of these women who were professional poisoners, started out as midwives and/or fortune tellers; both of which involve working at the threshold of the spiritual world (life and death). In their case, spirituality went in quite a different direction than the above mentioned paragons of truth, beauty, and goodness depicted by the Renaissance artists.

Madonna of the Book

Sandro Botticelli: c. 1480

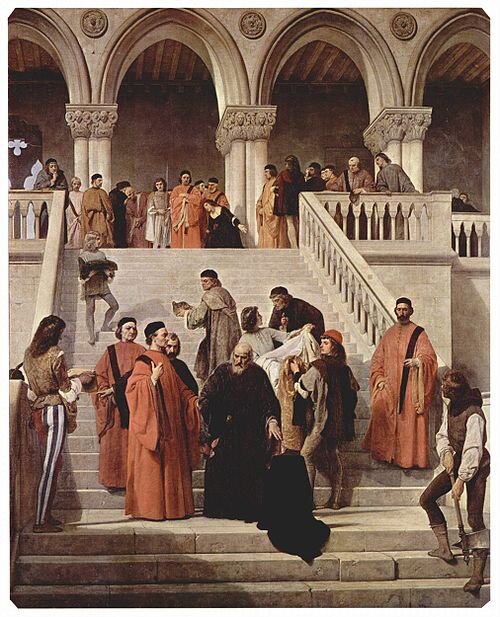

From left to right: "The Ten" in Francesco Hayez's The Death of the Doge Marin Faliero (1867); Catherine de Medici, Queen Consort of France, 1519 - 1589; Catherine Deshayes, ‘La Voisin’; professional poisoner and fortune teller, 1640-1680

Common use of language itself acknowledges that spiritual entities (things that we can’t perceive with physical senses such as thoughts, feelings, and will impulses) can act as poisons both in the environment and in our inner lives. Consider the following sentences:

1) ’His tendency to force his own agenda on others poisoned the aims of any group he joined.’

2) ’Changing the rules to include compulsory participation poisoned the natural enthusiasm the workers had for the project.’

3) ’My love for her was poisoned and eventually died due to the slanderous lies they told me about her.’

Anthroposphical medical science characterizes poison as something which, even though it may have a constructive purpose in the spiritual world, when it is pulled down into the physical world, it behaves destructively. For example, having a voracious appetite for learning new facts is usually a helpful, constructive quality; in contrast, if this acquisitiveness drops down into the physical realm, it becomes hoarding or stealing. An idealized love for innocence in the realm of thought and feeling is healthy; when it is pulled too far down into the physical realm, it may become the horror of child sexual abuse. Our relationship to the past and the future is related to spiritual capabilities in that we can’t physically sense what lies there. Therefore, when either the past or the future is pulled inappropriately into the present in a sense perceptible way, it can act as a poison. Racism and other kinds of baseless xenophobia could be examples of the former; a young child (i.e. prematurely) driving a car or drinking alcohol is an example of the latter.

A plant that is poisonous, such as the Belladonna with its shiny black berries and its flowers that turn away from the sun pointing towards the depths of the earth, has an animal-like feeling about it - a soul-like quality. In other words, this poisonous plant has pulled something down into itself that normally belongs in the ‘higher’ animal world so that it is ‘more spiritual’ than a non-poisonous plant. However, the deadly nightshade, as with other poisonous plants such as Hyoscyamus (Henbane), Digitalis (Foxglove), and Colchicum (Autumn Crocus) are also used as life-saving medicines; but only in very specific situations (certain illnesses), and even then only in small doses individualized to a particular patient. This is also true of certain mineral poisons such as phosphorous, mercury, and arsenic. Special cases include uranium and radium; minerals which produce a toxin (radiation). Mold is another exceptional case in the world of toxicology; it also becomes productive under threatening circumstances by off-gassing mycotoxins many of which are extremely destructive to human health. This act of producing something which becomes destructive independently of its creator, is also a quality that is usually associated with higher spiritual realms.

From left to right: Belladonna (Deadly Nightshade); Datura stramonium (Jimson Weed); Digitalis purpura (Foxglove); Colchicum autumnale (Autumn Crocus)

It did not take long for this attempt at characterizing poisons to lead into contradiction and even along controversial paths; even though that was certainly not the intent! Spiritual questions of good and evil, practical questions of health and illness, and even the primeval questions of male and female seemed to run into each other headlong at every turn; for better or for worse. Some thing or process can be used egotistically to promote personal welfare at the expense of another, or that same something or process may be used selflessly to promote the welfare of another. The same substance or process that poisons in a given time, place, or quantity, acts medicinally under different circumstances. The dark underbelly of the archetypal imagery of feminine wisdom, beauty, and virtue in its relationship to poisoning invites the pondering over the relationship between good and evil in general. Whether it is inner intent/motive, outer circumstances, or orientation of action; each of these factors, when adjusted one way or the other, can change the whole picture.

Virgin of the Rocks

Artist: Leonardo da Vinci (pictured to the right)

Year 1483–1486

Here are a few suggestions for understanding the role that toxins play in your life:

1) The first substance that many people consume upon arising is coffee or black tea; both of which have been used historically as a partial antidote to some plant poisons (if it is drunk during a meal). There have also been studies linking coffee with less chance of developing type 2 diabetes (but not necessarily with better blood sugar control for people who already have that diagnosis). However, coffee is one of the foods more likely to contain dangerous mycotoxins (toxins that are made by mold). Some companies, such as Bulletproof Coffee, test their product for mycotoxin safety. One clue that mycotoxin contaminated coffee may be a problem is if, instead of wakefulness and increased focus, you feel hyped up, jittery and foggy headed after drinking your morning treat.

2) It is possible for a sense perception to become a poison. One example is when too much time is spent in front of screens. The accompanying electromagnetic field exposures are also known to be toxic; especially if the exposure is for many hours on a daily basis. One way to significantly reduce exposure is to hard wire your home devices and put your phone in airplane mode when not in use - most especially if you carry it on your body! If you need convincing or motivation to make these surprisingly simple changes, ask your holistic medical provider to lend you EMF meters for some self education; or better yet, confer with a building biologist. Check out our EMF safety resources here. Balance excessive screen use with time outdoors where your eyes can see for longer distances. Healthy experiences of the senses, such as a good conversation with another person, time outdoors in the beauty of nature, or spending time with healthy works of art or in-person listening to healthy music can counter balance the harm done by too much exposure to falsehood, ugliness, and harmful actions.

3) Indoor air quality; here mycotoxins come to the forefront yet again. You can check for the some of the most dangerous mycotoxins (of the trichothecene variety) with a laboratory analysis of your house dust. Ask our office for information about a sample collection kit which attaches to your vacuum cleaner. Remember that what is in your attached garage is likely in your house as well - especially if that is where the ‘fresh air intake’ for your furnace happens to be! Our website’s resources page also has a link to a house hunting guide with helpful tips on what to look for to avoid mold and other common household exposures.

4) Diet: Nightshades for people with type O blood is a common aggravator of arthritis; gluten avoidance is optimal for those with autoimmune illnesses or recovering from a toxic mold exposure; cow dairy, and gluten exacerbate mucus production for some people. Diet is very individualized and the ideal diet for a particular person even varies over the course of a lifetime. Sometimes these dietary differences are due to toxicity (molds or chemicals which commonly contaminate specific foods, such as the toxic mold Fusarium and corn, or ‘Aflatoxin’ a mycotoxin produced by some ‘Aspergillus’ strains of mold frequently contaminating peanuts) or genetic differences which make it impossible or much more difficult to metabolize certain kinds of foods. On the other hand, the immune system may have simply lost tolerance for certain foods, after an illness or toxic insult of any type which is no longer present. In other words, the body over- reacts against foods, organisms, or environmental allergens which otherwise are not doing harm. Low Dose Immunotherapy is a therapeutic technique which focuses on increasing immune tolerance rather than ‘desensitizing’ (quite a different gesture) or a ‘search and destroy’ mission. See our resource page for ‘LDI Basic Information’.

5) Time spent in nature tends to have a health-giving effect; but did you know that there is actually a minimum amount of time where stronger health benefits kick in? Florence Williams, author of The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier and More Creative (W.W. Norton, 2017), has spent time wondering why and how time in nature seems to heal physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. She also wondered whether the well-acknowledged positive effects would max out at a certain threshold. Participants in one study found that, ‘Participants were much more likely to report good health and high well-being once they surpassed the 120-minute mark. (In fact, those who spent between one and 119 minutes outside per week reported the same amount of well-being as people who spent no time outdoors at all.) Benefits seemed to peak at between three to five hours, with no additional gain from more hours outside. This was true for people of all ages, including older adults and people with long-term health issues’. The positive effects were only experienced when people did not take their electronic devices along with them. These and other interesting findings and tips may be found on her blog. She also experienced and found studies relating to a ‘three day effect’ which additionally noted improved creative thinking and insight.

Note 1: ‘The records of the city councils of Florence, particularly those of the infamous Council of Ten of Venice, contain ample testimony of the ample use of poisons. Victims were named, prices set, and contracts recorded; when the deed was accomplished, payment was made.’ Casarett & Doull’s ‘Toxicology’ 8th ed. p.4

‘Wherever we strive to enter higher realms we have to reckon with living, not dead truth, and the living truth bears within it its own counter-image, just as in physical existence life bears death within it.’

Rudolf Steiner; The Karma of Untruthfulness, vol 1